This guest post is contributed by Christopher K. Starr. Starr was born in Newmarket, Ontario, but has spent the bulk of his adult life in the tropics of Asia and the Caribbean as an entomologist.

These are some reminiscences of my early years in an unwavering Quaker family. They are reflections on a way of life that was once a major part of some English-speaking societies but has now largely passed from among us. It was already fading when I was a child. The title is a mild play on words drawn from the formal name of the Quakers, the Society of Friends.

In the beginning:

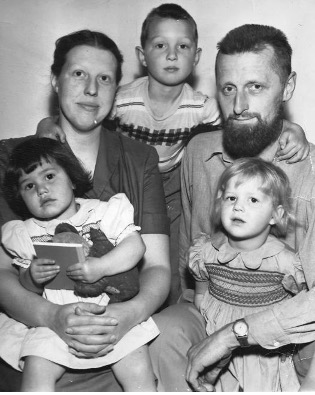

My father, Francis Starr (1916-2000) was from a traditional conservative Quaker family near Newmarket, Ontario. His schooling ended after one year of high school. Formal education did not especially engage him, and it was during the Depression. He thought it would be better if he were out earning. Still, he remained an avid reader and discussant his entire life, and we can fairly call him an intellectual. If I were to seek a single phrase to say what he was all about, I would call him a peace activist.

My mother, Dorothy Schlick Starr (1922-1977) came from a Methodist family in Iowa, but after they were married she had no difficulty transferring into the Society of Friends. (To call it a “conversion” would be regarded by all concerned as misleading and rather vulgar.) She was a nurse with an MA in Nursing from Yale University, and after moving to Canada she worked in the health profession and made use of her administrative acumen in various tasks for Canada Yearly Meeting.

My parents were believers, but I would not say that either was especially religious in the common-speech sense. They had met as relief workers in India and Pakistan, Francis with Britain’s Friends’ Service Council (FSC) and Dorothy with the American Friends’ Service Committee (AFSC). I was already an adult when I learned that that these two organizations shared the 1947 Nobel Peace Prize back when it was not yet hopelessly compromised. I expect my parents were aware of this, but I don’t recall either of them ever mentioning it. At the time that they met, Francis had already spent two years in China with the FSC’s Friends’ Ambulance Unit in what was plainly his personal heroic period. In India, Dorothy was for a time seconded to Mohandas Gandhi’s household as a nurse. They were both great admirers of Gandhi.

As a result, my younger siblings and I grew up in a household with a strong sense of social activism as an integral component of Quakerism.

In 1954, when I was four years old, our family moved to a house adjacent to my paternal grandparents’ farm on which my father had spent his early years. My grandparents were Elmer (1881-1973) and Elma McGrew Starr (1890-1985). A stand of stately elm trees flanking the entrance to the farm, which was cleverly known as Starr Elms.

One cannot be sure at this remove, but it feels like I spent more time on the farm up the hill than at our own house. Certainly, I have many more and stronger memories from the farm. To me, it was a grand place, and when we moved away shortly before my seventh birthday I felt like I had been cast out of paradise. Dylan Thomas’s “Fern Hill” probably resonates more strongly with me than any other poem.

My grandfather was an affectionate but stern man with a distinctly patriarchal manner. I especially noticed this when he read the Bible out loud. In particular, when reading from the Old Testament his voice would drone up and down, while I sat there transfixed by how utterly prophetic he sounded. At the risk of offending some kinfolk, I would say that he struck me as quite mechanical in his religious responses, while my grandmother seemed more creative. She was a nature lover, who introduced me into a lifelong interest in insects.

We worshipped at the Yonge Street meeting house, now recognized as a historical site. When I last visited it a few years ago it seemed not at all changed from how it had been in my childhood. At some times of year, if no others were expected at meeting and the weather was not clement, we would hold meeting in the Starr Elms parlour. Although we children were not praying, and an hour is a long time at that age, the warm sense of familial closeness and the hypnotic ticking of the tall grandfather clock made the occasions quite pleasant.

Sunday (First-Day) was of course not a day to work or to cause others to work, except for chores that could not be postponed. Livestock must be fed and cows milked, but crops were not to be planted or harvested on that day. I loved to hunt groundhogs with a .22 rifle, but this was forbidden on Sunday. I don’t know whether it was because groundhogs were regarded as vermin, so that exterminating them counted as work, or just that the discharge of firearms seemed unsabbathly.

To Ottawa:

Shortly after my seventh birthday in 1956 we moved to Ottawa. Together with the family of Gordon & Betty McClure, we went at the urging of the Yearly Meeting in order to serve as the nucleus of a new monthly meeting. Ottawa had several Quakers or persons who wished to become Quakers, but the organizing service of experienced Friends was needed. One could say that the two sets of parents felt a calling.

For the next year the Starrs and McClures lived as one family in a big house in the Glebe neighbourhood. I don’t know the details, but we were apparently a coop or collective. The elder McClures were teachers, who did not draw a salary during the summer months, and I once heard my father mention to an acquaintance that they supported us in the winter, and we supported them in the summer. As far as I know, it was never the plan that this should be a long-term arrangement, and after a year we occupied separate houses.

I would not say that I felt isolated or in any way alienated in Ottawa, although I had only infrequent contact with Quakers outside of my own family and the McClures. Still, I admit that I sometimes felt a bit awkward at the oddness of being a Quaker in a sea of those who were not. Without making too much of it, at times I vaguely regretted that we were not something more “normal”, like Methodists or Anglicans. In white Protestant North America that was about as normal as it got.

Olney:

This changed abruptly when, at the age of 13, I went to attend high school in Ohio. The Friends’ Boarding School (now Olney Friends’ School) was established by Ohio Yearly Meeting (OYM) in 1837 and had apparently been known informally as Olney throughout. There I became conscious for the first time of being part of a long tradition. Elma Starr attended Olney, as did my father (for one year) and his two sisters, and so did I and all of my siblings. We chose to go there. The historic, imposing Stillwater Meeting House was at one end of the campus, and every week we went to meeting there along with the local Friends. William P. Taber in The Eye of Faith relates how Quakers in Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio once formed such a substantial society that it could be almost self-containing to many.

As detailed by Arthur Dorland in The Quakers in Canada, Canada Yearly Meeting is an outgrowth of Ohio Yearly Meeting. In one sense, at Olney I immediately felt right at home. In another way it was quite a different milieu. For one thing, I was surrounded by Quakers in everyday life (although Olney also took in students of backgrounds). For another, the conservative Quakers of Ohio (including some of our teachers) manifested a distinctly stronger sense of tradition than did those in Ottawa. At least in many of the older Friends from the local meeting, one could see this at a glance. While in Ottawa we dressed like normal people, including on Sunday, some in Ohio dressed in what I learned was the plain manner.

There was also the matter of plain speech, the most salient manifestations of which were the use of thee for the second-person singular (similarly thy and thine) and the days of the week and months of the year named by number, avoiding even the most casual invocation of pagan deities. My grandparents addressed as “thee” all whom they knew personally. My father used this form with all family members and other Quakers. My own habit was to use it only with older Quakers and the few of my generation that I knew preferred it. However, in conversing or corresponding in French, German or Spanish I have a decided preference for tu/du/tú; an advantage of my present advanced age is that I am almost always older than the other person and so have liberty to go to the familiar form.

Quakers have always laid much emphasis on education. Olney’s scholastic strengths, I would say, were not only on religion but also on history and language, including English. It was there that I got my start toward being a good Spanish speaker, and through the school’s exchange programme with our sister school in Gaienhofen-am- Bodensee I gained fluency in German through spending the 1965-66 school year there.

Lying outside the town of Barnesville, Olney had a definite feeling of apartness. We did not see ourselves as a part of the town, and the school administration evidently wanted it that way. During my four years there, I hardly knew any of the town’s residents personally, and I regret that I never went to the trouble to ask them how they viewed the school. It was not a state of mutual hostility, just going different ways.

At that time, then, Olney was still strongly stamped by the Ohio Yearly Meeting (OYM) and conservative Quakerism. I believe that most of my Quaker schoolmates were on much the same page as I was. We are the last generation with a familiarity with traditional quaker customs of daily life. We would not be baffled if we were magically set down in Ohio in the earlier age described by Bill Taber.

However, already in my childhood such things as plain dress, plain speech and the separation of women and men on different sides of the meeting house were coming to have an archaic feel. While not alien to us (at least in Ohio), they were something that we associated more with earlier generations than ourselves. Although there were still many women who wore the traditional bonnet in the Ohio strongholds of conservative Quakerism, I believe my grandmother was the last in Canada who still wore it as a matter of course. If my sisters or cousins wore it, it was a fun exercise in exoticism, not a badge of who they were.

I will mention one other thing that struck me at Olney. I arrived entirely ignorant that Quakerism in the USA was and is divided into three autonomous tendencies known by their founders’ names. The three had been re-united into a single Canada Yearly Meeting soon after I was born, so I didn’t even know that there was more than one kind of Quaker. (Again, see Arthur Dorland’s book.) The school was a creature of the OYM of the Wilburite tendency. However, the Hicksite tendency is so similar to it that I wasn’t aware until years later that some of my schoolmates were of this persuasion. On the other hand, I don’t believe there were any Gurneyites among us. One can fairly say that the Gurneyites had departed much more from the practice of traditional Quakerism than had the other two, and we didn’t consider them authentic. The fact that Richard Nixon was from a Gurneyite family sufficed to consolidate this attitude.

A secular Quaker looks at himself:

I was never especially spiritual, and by my early 20s I realized that religious feelings had entirely fallen away. No existential crisis, no dark midnight of the soul, nor any particular relief, just a feeling of some aspect no longer there. Even so, more than 50 years later I remain a conservative Quaker in a meaningful way.

Although Sigmund Freud was never religious — the non-practice extended back at least to his parents, I believe — he did not deny his Jewishness. I once asked my friend, the late Richard Nowogrodzki, whether his parents were very Jewish, to which he responded “Oh yes. Very Jewish and very atheist.” That made perfect sense to me, as they did not lose their ethnicity by taking off the cloak of Judaism. The Freuds and the Nowogrodzkis were secular Jews, a well-known concept.

We are like the Jews in some ways, although of course we have not been persecuted as recently or as severely they have. And even if the term is unfamiliar to most or all readers, I and most of my same-generation relatives are secular Quakers. That is, we partake of a certain ethos and even some manners that came from our lineage.

What are these? Foremost is a social consciousness, including egalitarianism. I don’t know whether Quakers had a large role in the American Civil Rights Movement, but we were unhesitatingly in favour of it. A little while later came at least passive acceptance of equal opportunities for women. Equal rights for gays and lesbians came later.

And what about religious tolerance? This is very easily answered. Tolerance is almost total. I observed this at Olney, as well as on many occasions elsewhere. A rather striking example arose around the time I was 12 or 13. My father, knowing that some of my friends sang in the Anglican Church, remarked to me one day “Why doesn’t thee go down to St Matt’s and join the choir?” Which I did. (Disclosure: Unlike most in the all-male choir, I could not read music and was not much of a singer. One wonders if I contributed to the drop in church membership.) He evidently thought it would be good for me and was not in the least concerned about doctrinal differences or that on Sunday mornings I would be in church and not in meeting.

When I am asked what my parents were doing in Asia in the 1940s, I usually say that they were medical missionaries. This is close enough in a list of jobs, but it can also be very misleading. Quakers almost never proselytize, and FSC and AFSC were no exception. If asked about their motivation, the answer would certainly have been that it was a Christian’s duty to alleviate suffering. While other religious organizations undertake medical missions as a way of fishing for converts, in the FSC and AFSC this would have seemed quite vulgar. Friends were happy to embrace new members, but they would have to come to us. I suspect that this overall disinclination to proselytize has been a major contributor to Quakerism’s increasing reduction in size and influence in the face of vigorous competition.

And tolerance of internal heterodoxy? I once heard the question raised at a Young Friends forum whether a Quaker could be an atheist. I don’t recall that the question got much traction, but the fact that it was not dismissed out of hand tells us something. I was never privy to the discussions of membership applications in the Society of Friends, but I rather suspect that one could be a Quaker in good standing without an explicit affirmation of faith as long as one was discreet in one’s near-agnosticism. This is in contrast to the time when the great naturalist John Bartram (1699-1777) was expelled from his meeting in Pennsylvania for denying the divinity of Jesus.

The most lasting stamp of my Friendly childhood is probably a serious attitude toward language and utterances. One said what one meant and meant what one said. Or, as my father expressed it on several occasions, “Let thy yea be yea, and thy nay be nay.” One day when I was perhaps four years old, my grandmother was making apple sauce. She gave me a taste of it before she put in the sugar, and I remarked that I liked it better that way. Later, if she was making apple sauce she put an unsweetened portion aside for me, telling people that “Christopher prefers it like that.” Even at that age it was assumed that if I said it, I meant it. Part of our family’s legend is an occasion on which a workman exclaimed “Well, I’ll be damned.” Grandma’s instant reaction was a mild “I hope thee won’t.” However, another part is her sly dictum (which one of my uncles loved to quote) that “Thee can tell the truth without telling everything thee knows.”

I have never been able to accommodate to some other peoples’ indifference to language. As an example, I was once riding in a bus in the Philippines with a prominent “No Smoking” sign at the front. When another passenger lit up I leaned over and, squinting as if not seeing very well, asked him if he could read that sign for me. Without a touch of irony he told me it read “No Smoking”. Let me note that I didn’t care whether he smoked, I just objected to this indifference to language.

Analogous to this respect for language, at least on an emotional level, is a distaste for ostentation, including in personal adornment. I well recall that, when we moved to Ottawa and I was around Catholics for the first time, I found the earrings and other decorations of even many very young girls vaguely unsettling.

In the early days in England many Quakers, being excluded from the universities and some professions, went into business, some with marked success. (All readers will have heard of Cadbury’s chocolates.) An undoubted contribution to this success was Quakers’ reputation for fair dealing, along with a tendency toward frugality. One did not waste capital on frivolous things. This tendency has come down to those of us who are not in business. I am perhaps a rather extreme example of this, something about which all of my ex-wives complained.

Quakerism is traditionally associated with sobriety, and I am confident that my grandparents and those before them never had a drink or a smoke in their lives. The explanation that I heard as a child was that one ought never to be intoxicated in case the “Still Small Voice” of God spoke to one. However, I suspect that it was more about maintaining a clear view of the world and one’s place in it. This is one aspect of my heritage that has largely been lost over the last couple of generations. I doubt that there are many teetotalers among today’s secular or even religious Quakers, although habitual drunkenness or heavy smoking seem to be unknown.

Similarly, we seculars do not observe the Sabbath or First-day. And, while we oppose going to war, for the most part we are not pacifists. We understand the Peace Testimony that some see as the heart and soul of Quakerism, but we do not uphold it. Many of my male schoolmates at Olney registered as conscientious objectors and so did Alternative Service. I could be wrong, but I suspect that some blushed inwardly as they did so. At that time membership in one or another meeting served as a convenient get-out-of-Vietnam card, regardless of whether one really, truly objected to all bearing of arms.

It would be dreadfully snobbish to imply that any of these features is peculiarly mine or ours. Still, in a real sense in my secular senior years I have never stopped being a Quaker.

Leave a Reply